Security requirements for Web applications are vital because they are specifying what a team (e.g. a development team) has actually to do and what not. Many companies are however struggling with implementing such requirements for Web-based applications, at least consisting ones on an organizational level. There are many reasons for that: complexity, lack of know-how, fast-changing threat landscape…

As a result, we very often find inconsistent, outdated, or completely useless requirements in companies that cannot be implemented or (even worse) that lead to insecure implementations. In the practice, I find that existing security requirements are very often just ignored by the development teams and replaced with their own ones. This may become really problematic from a security perspective, not only since it relies on the experience of certain developers.

I, therefore, had the idea to create a template that companies can use to implement their own Web security standard. I finished the first Version in May 2014, but it took me another 2,5 years till I found it has reached a certain level of maturity to translate the original German version into English. Version 1.3 of the template for a Technical Security Standard for WEB-based applications and services (TSS-WEB) is now available as both MS Word and PDF.

The requirements in this document mostly relate to common best practices that define a baseline level of security for Web-based applications and services. You adapt it to your needs and your environment by removing existing requirements, adding new ones, or changing existing ones, e.g. in respect of their rigor that is specified of each requirement based on RFC2119 terminologies like MUST or SHOULD:

This allows you to be very specific about what is actually mandatory and what are recommendations for a project. In addition, you find protection classes defined and used in the document, that allow you to distinguish requirements of the levels of their rigor in respect of an application risk profile (e.g. is it Internet-facing or just internal).

You may use this as a template for your own company-wide or team-specific standard or just use those requirements that you need and change them if they do not suit your environment.

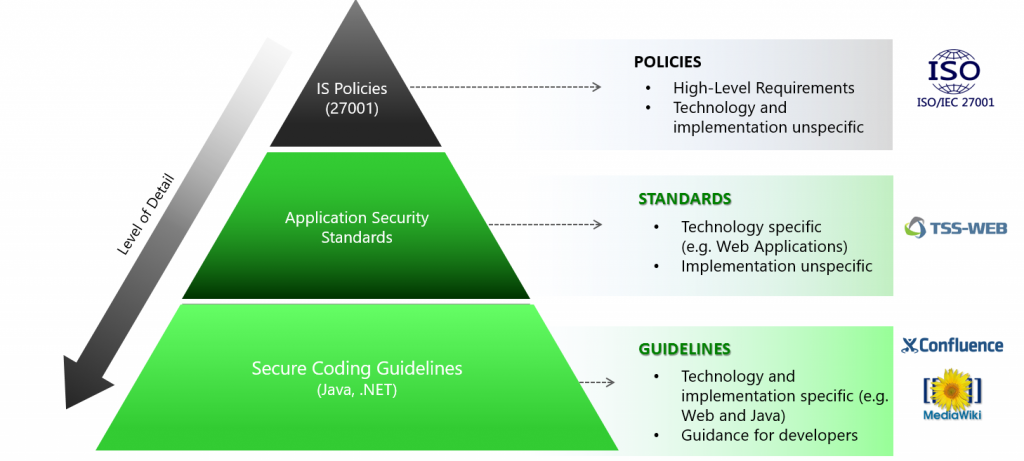

Note that this is just a high-level technology-specific standard that is focused on Web-based applications and services in general. It is not mixed up with Java or PHP code on purpose. Because these implementation-specific topics will change a lot in the practice (e.g. when you introduce a new framework) so that it makes more sense to maintain such implementations for your standard for Java, .NET, PHP, etc. with code snippets and details programmer centric explanations in separate secure coding guidelines. Wikis such as Confluence work really great for this because they are less static, can be referenced in ticket systems, and fit into the way many developers are used to working.

In the end, you will end up with a security requirement pyramid like the following:

The more you go down the pyramid the more specific requirements become (e.g. high-level, related to Web applications, related to Java-based Web applications). With a standard in the middle of this pyramid-like TSS-WEB, you can ensure a certain level of security but provide your developers the flexibility they need.

Document owner of the standard should be the security department that updates it at least once a year whereas the ownership of the secure coding guidelines can be transferred to the development teams – because in this scenario, security is not defined within the guidelines, they are “just” implementation of the standard.